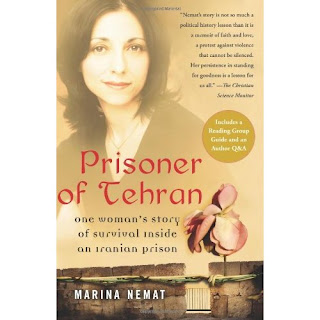

After watching interviews with Marina Nemat of Toronto, I was very moved and impressed to read her harrowing yet compassionate memoir, Prisoner of Tehran. She is a beautiful and poetic woman who writes of an idyllic childhood under the Shah followed by the shattering of her world during the Iranian Revolution. At sixteen, she relates, after criticizing the new regime in high school, she was arrested, tortured and sentenced to death, only to be reprieved at the last moment, but at a terrible personal price...

Her unusual perspective, as a Catholic Iranian of Russian extraction, makes the story especially interesting. It also lends ominous depth to her theme that revolutions often fail to deliver on their promises, since her family had already suffered from the bitter fruits of Bolshevism. As human rights advocates often approach matters from a more secular perspective, her emphasis on her faith is quite special. Her frank but sad admission of having betrayed her religious beliefs by officially becoming Muslim under duress is very honest, humble and poignant. She has stated in interviews that she grew up hearing of the lives of Christian saints and martyrs, and that it was awful to realize, under torture, that she would be willing to do anything, even sell her soul to the devil, in order to escape the pain and go free.

The same very human, relatable woman, claiming no extraordinary heroism, comes across in this book, although she seems heroic nevertheless. Her capacity to resist despair, her persistence in hoping and trusting in the mercy of Christ, and her generosity in loving and caring for others are wonderful. Her description of conceiving a child by her interrogator and rapist, who had forced her to marry him, and nonetheless being able to recognize the innocence of the child, is particularly touching. While I disagree with some of her radically pacifist statements, I appreciate her general point that it can be hard to judge people, even deadly enemies, since human beings are often such mixtures of good and evil.

Welcome to 'Lost in the Myths of History'

It often seems that many prominent people of the past are wronged by often-repeated descriptions, which in time are taken as truth. The same is also true of events, which are frequently presented in a particular way when there might be many alternative viewpoints. This blog is intended to present a different perspective on those who have often been lost in the myths of history.

Showing posts with label catholicism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label catholicism. Show all posts

Thursday, 26 July 2012

Tuesday, 21 February 2012

The Crown

Nancy Bilyeau's debut novel The Crown takes readers on an odyssey through the England of Henry VIII during the bloody period of the dissolution of the monasteries as seen from the point of view of a young Dominican novice. There are many aspects of this extraordinary novel that contemporary Catholics will find that they can relate to, namely the confusion in the Church and the compromises of many of her members to political persecution and social expediency, as well as the heroic stand taken by those with the courage to speak truth to power. In Tudor England, speaking truth to power, or even silently trying to follow one's conscience, often meant dying a hideous death. Young Joanna Stafford finds that in those intense times there is no such thing as spiritual mediocrity; either she must take the high road or face perdition. Joanna is not one to settle for less than heroism anyway, having entered a strict Dominican monastery where she looked forward to an austere life of poverty, chastity and obedience. When she leaves the monastery without permission to help a relative who is condemned to death for championing the Catholic faith, she sets off a chain of events which lead her on a spiritual journey into the heart of the mysteries of faith, of sacrifice, and of royal power.

The title of the book signifies a mysterious relic, the crown of a holy Saxon king, which Joanna is commissioned by the wily Bishop Gardiner to find for purposes of his own. Joanna knows that not finding the crown could mean the torture and execution of her father, who already languishes in the Tower of London.Yet, along with the elusive and tangible crown, there are many other awe-inspiring crowns in the novel, the crown of martyrdom, the crown of virginity, the crown of Our Lady, the blood-splattered Tudor crown, the pagan crown of ancient monuments at Stonehenge, the crown of the foundations of a lost monastery and the Crown of Thorns. Even as the symbolism of the crown is repeated throughout the novel, so Joanna finds her vocation tested as she learns to overcome her worst fears. It is a story in which spiritual victory comes as the fruit of earthly defeat.

One plot element in The Crown involves a series of famous tapestries which hold clues to solving several puzzling scenarios. Even as the tapestries are woven by the nuns at Dartford Priory, the author has woven her story so that many clues hidden in the narrative, which make the novel a mystery and a thriller as well as an intriguing work of historical fiction, containing many details of monastic existence and of the struggles of the poor in the sixteenth century. It is refreshing to see the Reformation from a Catholic point of view, one reminiscent of Robert Hugh Benson. I came away from the book marveling at how God's plan is like a vast tapestry of which we only see a tiny portion and yet every thread has a distinct purpose. Through her stumbles and falls, Joanna is confronted with her own weakness yet she rises with new strength, gaining insights which help her to see beyond the surface of things.

Here is my interview with the author Nancy Bilyeau.

(*NOTE: The Crown was sent to me by the publisher in exchange for my honest opinion.)

Saturday, 20 August 2011

The Faith of Leopold III

There is a strange idea in circulation that King Leopold III of the Belgians (1901-1983) was not a devout Catholic. In fact, the Belgian kings, in general, are sometimes portrayed as lacking spiritual fervor until Leopold's son, King Baudouin. I was shocked to read, in one account of Baudouin's life, that Albert I and Leopold III were "lukewarm" Catholics, unlike Baudouin, whose deep faith was presented as a remarkable departure from family tradition. Other authors have tried to explain the so-called "estrangement," beginning around 1960, between Leopold and Baudouin, in terms of a conflict between the supposedly more secularist outlook of King Leopold and his second wife, Princess Lilian, and the piety of King Baudouin and his Queen, Fabiola de Mora y Aragón, whom he married in 1960.

The cooling of relations, previously warm and affectionate, between Leopold and Baudouin, following the departure of Leopold and his second family from Laeken in 1960, and their move to the country estate of Argenteuil, was, in fact, largely due to reasons of state. Leopold's presence undoubtedly aided and reassured his son, during the early years of his reign, especially since Baudouin ascended the throne as an inexperienced and vulnerable young man of 20. Once Baudouin achieved sufficient maturity, however, political necessity obliged father and son to keep a certain mutual distance. Close family relations provoked charges that Leopold had not truly abdicated but was continuing to rule through his son. As Michel Verwilghen describes in Le mythe d'Argenteuil, demeure d'un couple royal (2006), a number of King Baudouin's advisers were determined to distance the young monarch from his father and his step-mother, Princess Lilian. It is also true that misunderstandings and personal conflicts within the royal family fed the process.

As far as religious differences are concerned, Lilian did not favor the charismatic movement, with which Baudouin and Fabiola eventually became involved. Apparently, Leopold was strongly opposed to the Belgian Primate, Cardinal Suenens, who gained considerable spiritual influence over Baudouin. Yet, the idea that Leopold was a "lukewarm" Catholic is false. Leopold's father, King Albert I, was also far from "lukewarm"; he was, in fact, deeply pious. Albert took pains to inculcate his own religious devotion and critical conscience in his children. "As you nourish your bodies," he told them, "so you ought to nourish your souls" (quoted in La Regina Incompresa, tutto il racconto della vita di Maria José di Savoia, 2002, by Luciano Regolo, p. 22). Leopold appears to have inherited a good measure of Albert's faith.

From his youth, Leopold displayed a touching religious sense. Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, the twelve-year-old Prince wrote to his father, under German siege in Antwerp: "Every day I pray the good God to help us and enable us to return to you very soon"(quoted in Léopold III, 2001, by Vincent Dujardin, Mark van den Wijngaert, et al. p. 22). As a young man, according to a close companion, it was Leopold's "Christian charity" which inspired his concern for the poor (see Léopold III, sa famille, son peuple sous l'occupation, 1987, by Jean Cleeremans, p. 13). Leopold's faith was also demonstrated, under tragic circumstances, upon the death of his first wife, Queen Astrid. Leopold's secretary, Robert Capelle, related in his memoirs that, after the terrible car accident in Switzerland,the grief-stricken King confided to him: "Why did the good God take her away from me? We were so happy...she is still so, but me...how I need her to protect me!"

In The prisoner at Laeken: King Leopold, legend and fact (1941), written to defend the King from charges of treason during World War II, Emile Cammaerts noted that he was probably playing into the hands of Leopold's enemies, by emphasizing the role of religion in his life, as expressions of piety could easily be interpreted as signs of weakness or hypocrisy. Yet, Cammaerts insisted, Leopold (and his father, Albert) could only be understood in terms of faith put into practice. In support of his claim, Cammaerts quoted several passages from Leopold's speeches to the Belgian clergy. In 1936, Leopold declared:

The love of one's neighbors, the sense of duty, truth, and justice, if applied to daily life, would spare mankind countless sufferings, troubles, and anxieties... The solution to the problems which oppress the world can only be found in the practice of Charity between individuals and between nations.

Similarly, in his Political Testament, in 1944, the King would assert that "Christian charity and human dignity" necessitated extensive social reforms in Belgium. Cammaerts also recalled a conversation with the King prior to World War II, during which Leopold deplored the political divisions and abuses in Belgium, exclaiming: "And to think, that we call ourselves Christians!"

Another biographer, discussing the King's interests in nature, travel and exploration, asserts: "Deeply religious... he found, in nature, the presence of the Creator God" (Léopold III, 2001, by Vincent Dujardin, Mark van den Wijngaert, et al. p. 338). This account certainly does not over-idealize Leopold, portraying him as upright, but stubborn and authoritarian. Therefore, I do not think there can be any question here of "hagiography" of the King.

In 1983, Kagabo Pilipili, an African student, and his wife were received by Leopold at Argenteuil. During the audience, Pilipili's wife mentioned her son's heart problems, and Leopold immediately promised the aid of Lilian's cardiological foundation in obtaining treatment for the child. As Leopold's own son, Alexandre, had suffered from heart problems, he was especially sympathetic to the family's plight. When Pilipili and his wife thanked the King for his assistance, he replied, in a tone of deep emotion: "I will do what I can. But God will do the rest for you." Leopold's guests were greatly touched and consoled by his belief in Providence (see Léopold III, homme libre, 2001, by Jean Cleeremans, pp. 57-58).

While none of this means that Leopold III was a saint or a perfect individual, it would certainly be false to say that Baudouin was the first Belgian king to be sincerely religious.

While none of this means that Leopold III was a saint or a perfect individual, it would certainly be false to say that Baudouin was the first Belgian king to be sincerely religious.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)