As a follow-up to my last post, here is an interview with Marina Nemat, dealing with her second memoir, After Tehran, and her thoughts on the potential for regime change in her native Iran.

Welcome to 'Lost in the Myths of History'

It often seems that many prominent people of the past are wronged by often-repeated descriptions, which in time are taken as truth. The same is also true of events, which are frequently presented in a particular way when there might be many alternative viewpoints. This blog is intended to present a different perspective on those who have often been lost in the myths of history.

Tuesday, 31 July 2012

Thursday, 26 July 2012

Marina Nemat

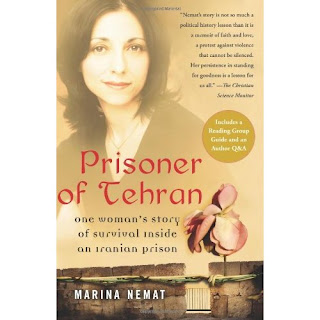

After watching interviews with Marina Nemat of Toronto, I was very moved and impressed to read her harrowing yet compassionate memoir, Prisoner of Tehran. She is a beautiful and poetic woman who writes of an idyllic childhood under the Shah followed by the shattering of her world during the Iranian Revolution. At sixteen, she relates, after criticizing the new regime in high school, she was arrested, tortured and sentenced to death, only to be reprieved at the last moment, but at a terrible personal price...

Her unusual perspective, as a Catholic Iranian of Russian extraction, makes the story especially interesting. It also lends ominous depth to her theme that revolutions often fail to deliver on their promises, since her family had already suffered from the bitter fruits of Bolshevism. As human rights advocates often approach matters from a more secular perspective, her emphasis on her faith is quite special. Her frank but sad admission of having betrayed her religious beliefs by officially becoming Muslim under duress is very honest, humble and poignant. She has stated in interviews that she grew up hearing of the lives of Christian saints and martyrs, and that it was awful to realize, under torture, that she would be willing to do anything, even sell her soul to the devil, in order to escape the pain and go free.

The same very human, relatable woman, claiming no extraordinary heroism, comes across in this book, although she seems heroic nevertheless. Her capacity to resist despair, her persistence in hoping and trusting in the mercy of Christ, and her generosity in loving and caring for others are wonderful. Her description of conceiving a child by her interrogator and rapist, who had forced her to marry him, and nonetheless being able to recognize the innocence of the child, is particularly touching. While I disagree with some of her radically pacifist statements, I appreciate her general point that it can be hard to judge people, even deadly enemies, since human beings are often such mixtures of good and evil.

Her unusual perspective, as a Catholic Iranian of Russian extraction, makes the story especially interesting. It also lends ominous depth to her theme that revolutions often fail to deliver on their promises, since her family had already suffered from the bitter fruits of Bolshevism. As human rights advocates often approach matters from a more secular perspective, her emphasis on her faith is quite special. Her frank but sad admission of having betrayed her religious beliefs by officially becoming Muslim under duress is very honest, humble and poignant. She has stated in interviews that she grew up hearing of the lives of Christian saints and martyrs, and that it was awful to realize, under torture, that she would be willing to do anything, even sell her soul to the devil, in order to escape the pain and go free.

The same very human, relatable woman, claiming no extraordinary heroism, comes across in this book, although she seems heroic nevertheless. Her capacity to resist despair, her persistence in hoping and trusting in the mercy of Christ, and her generosity in loving and caring for others are wonderful. Her description of conceiving a child by her interrogator and rapist, who had forced her to marry him, and nonetheless being able to recognize the innocence of the child, is particularly touching. While I disagree with some of her radically pacifist statements, I appreciate her general point that it can be hard to judge people, even deadly enemies, since human beings are often such mixtures of good and evil.

Labels:

Canada,

catholicism,

Iran,

Iranian Revolution,

Islam,

Marina Nemat,

Russian Revolution

Friday, 20 July 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)